About Staffordshire

1810-1835

The geography of the Staffordshire region in central England helped to make it a center for producing various types of lead-glazed earthenware. Thick layers of clay lay only a few feet below the surface. There was so much clay within easy reach that 18th-century potters routinely dug clay right out of the roads, giving us the origins of the phrase “pot hole.”

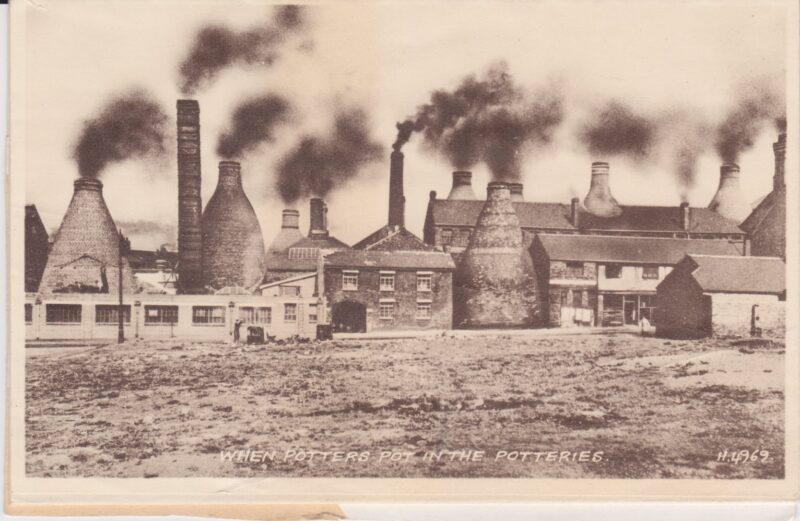

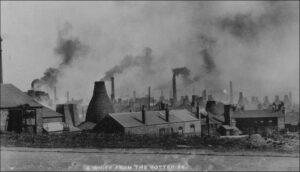

Staffordshire’s signature bottle kilns dotted the northern part of the Midlands district of the United Kingdom. The towns of Burslem, Fenton, Hanley, Longton, Stoke, and Tunstall, which are now called Stoke-on-Trent, covered roughly 100 square miles. The area came into focus as the powerhouse of pottery production in the UK in the 1700-1800s, but it had been a significant pottery producing area for centuries. Staffordshire has plenty of clay, lead, salt, and coal in the area making it a perfect place for pottery production. It’s thought that this first came together in 1467, 200 years before John Astbury introduced his red earthenware to the world, and almost 300 years before the “Potter to Her Majesty,” Josiah Wedgwood made his cream colored, lead-glazed Queen’s Ware for Queen Charlotte.

The antique Staffordshire ceramics that we are most familiar with today are from these later periods, when as many as 4,000 bottle kilns were in use, producing fine dinnerware and collectible figurines.

One of the leading potters of the 18th century was Thomas Whieldon, who made everything from black stoneware tea and coffee pots and knife hafts for the Sheffield cutlers, to plates with richly ornamented edges. Whieldon had many apprentices, Josiah Spode and Ralph Wood being two of the most important, and he was a business partner for about five years with Josiah Wedgwood, who learned a lot from Whieldon before establishing his own firm in 1759.

Though rightly famous for his creamware, which was lightweight and had a luminous glaze, Wedgwood also developed a line of unglazed black stoneware known as the basalts. Some wares had basketweave reliefs on their exteriors, others were decorated with terracotta figures he called Etruscan Ware. Other achievements by Wedgwood include the introduction of Jasperware, stoneware colored by metal oxides, and pearlware, a bluish version of his creamware.

By the end of the 18th century, Staffordshire potteries were producing Anglo-American wares for the newly independent American colonies. Pieces were often decorated with images that celebrated American independence.

At the beginning of the 19th century, transfer-printed scenes of everything from Niagara Falls to views of Boston Harbor were produced on monochrome blue platters and plates, now referred to as Historical Blue Staffordshire, or simply Old Blue.

Other wares made for the new American market were Gaudy Dutch, with vivid pink, green, red, and green glazes. And many patterns of sponged ware, called Stick-Spatterware, came out of the Staffordshire potteries to supply Americans with table, tea, toilet, and ornamental ware.

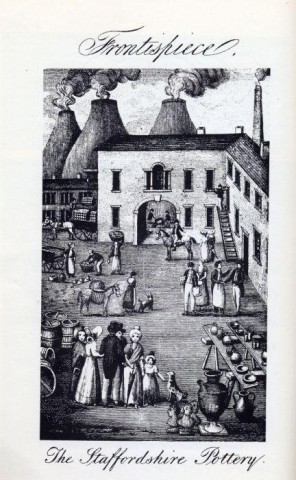

An etching of a 19th C. Staffordshire Pottery

works with bottle kilns burning in the background.

More realistic views of the Potteries at the close of the 19th Century –

“A whiff from the Potteries”